Ilya Milstein's infinitely creative universe

Path #11: The acclaimed illustrator on the highs, lows & lessons of his career

In this edition of Desire Paths…

Today, Ilya Milstein is an internationally respected illustrator. But it hasn’t always been smooth sailing. Below, Ilya shares his journey from Melbourne to Brooklyn, from a childhood comics-lover to a professional illustrator with clients like the New Yorker and Red Bull, and from the depths of mental health crises to the sustainable life he’s building today.

PLUS: Six hard-won lessons from his—and for your—creative career.

I’m Danny Giacopelli, an editor, photographer and small business fan. Desire Paths is based on the idea that the most fulfilled, fascinating people in the world chase after risky dreams, change careers, make unconventional decisions, and cross oceans to start something new. I go deep with them—business owners, designers, shopkeepers, farmers, billionaires, hermits, maybe even you—and share everything I learn. I’d love if you’d subscribe!

Path #11: Ilya Milstein

“Maintaining your passion is absolutely critical. If you get too tied up in making money, it will never feel like enough. If you get too tied up in being prolific, you’ll burn out and the quality of your work will suffer.”

I’ve admired Ilya Milstein’s intricate, playful, incredibly detailed illustrations for many years. Whenever I see his work in the wild—on Instagram, in the pages of The New York Times, in the campaign of a friend’s clothing label—I smile. There’s just something about them that makes me happy.

When I launched Desire Paths, I thought, Man, one day I’d love to know more about this Ilya guy. What’s his story? His process? His inspirations? And, dear reader, one of the joys of doing this newsletter is that I can actually answer those questions.

Here’s Ilya’s story, from the horse’s mouth. He shares his life journey, early big breaks in his career, challenges with mental health, and useful tips for young creatives. Enjoy.

—DG

Ciao Melbourne!

My grandparents were Russian and Polish Jews who emigrated to Australia after WWII. Although they were trained in other things, they ended up making a living, as a lot of Jewish immigrants did, by importing fabrics, weaving textiles and making garments. They did quite well—they furnished outfits for the Australian Olympic winter team for many years, had stores all over Melbourne, and were stocked nationwide. Because they had relationships with Italian mills, my father grew up going on work trips with his parents in the 1950s and 60s. He fell in love with Italy and eventually ended up moving there. That’s where I was born: in Milan, 1990. Although we moved back to Australia in 1993, and my memories of Italy are very faint, they still loomed large in my imagination as a kid.

From comics to architecture

I lived in Melbourne for the next 25 years. Growing up, I was very passionate about drawing and comics. By the time I was 18, I had drawn around 2,000 pages of comics. Melbourne had a booming zine culture then, so I broke into that when I was 15 or 16. I became something of a figure in that world by the time I finished high school. I loved it. I had a community of likeminded people who saw me in the terms I wanted to be seen.

But illustration in Australia was a nascent career path back then. The graphic culture wasn’t advanced, Australian comics were generally poor, and illustration just didn’t really exist. I wasn’t aware that in Japan and America and France, there were tons of opportunities to make a living doing drawings. So I never thought I’d be able to actually study art. Instead, I tried to be clever and study architecture, which I thought would be a middle ground between art and commerce. But of course, that’s not true. It’s its own thing entirely. And I learned after a year of studying that whatever it was, it wasn't for me. So I dropped out. I was 19.

Let’s go to art school

After that, I applied to study drawing at the Victoria College of the Arts, with a very full portfolio… and they didn't let me in. I probably had the wrong attitude. Young people often have an ego that goes unchecked and unchallenged. And that was one of the first times it was challenged. It sent me into a bit of a tailspin. Instead of studying that year, I ended up traveling and working and thinking about what to do next. I eventually applied again, this time to study sculpture and spatial practice, a conceptually-driven department. It wasn’t what I set out to do before, but it’s what I ended up doing for the next three years…

Aimless and confused

By the time I entered art school, I was 20 or 21, older than the other students, sheepish, and pretty confused. That whole period of my life—my late teens through my mid twenties—was defined mostly by aimlessness. I wasn’t keeping a healthy lifestyle. I was partying a lot and doing drugs, which wasn’t helping my mental state. At the same time, my work got some attention. I was included in a few museum exhibitions. And I exhibited externally and won a few international awards. But I just didn’t have satisfaction or conviction in what I was doing.

Is this it?

Graduating art school is terrifying. Unless, of course, you’re approached by galleries for representation or someone buys your work. I was making videos at that time, so selling wasn’t really an option. It wasn’t like London or New York where gallerists actually go to these shows. In Australia, the art market is very, very small. Of the 120 students in my year, I believe only two of them are still making a living as an artist full time right now. I saw what life was like for my older artist friends: constant grant applications, teaching gigs, residencies. It seemed chaotic. I have nothing against that, but I didn’t have the stomach for it or the conviction in what I was doing. So I was freaking out, wondering what I was going to do next.

Hitting rock bottom

In the two years after graduation, living in Melbourne, I worked a series of part time jobs, I exhibited my work, I had partners, friends and adventures. But there was a sense that I wasn’t laying the groundwork for a sustainable future. It gave me anxiety and fed an ongoing depressive cycle, which at that time was undiagnosed. Things came to a head when, in the period of a week, I had a messy breakup, I had a huge falling out with my best friend who was also my roommate, I was fired from one of my jobs, and I was in a position where, for the first time since my first year at school, I had no plans to exhibit my work. Things had dried up. It was a moment of crisis.

I’d always wanted to move overseas and I felt the years ticking away. So I thought I’d leave the house I shared with friends, move back to my dad’s place to save some money, then move overseas when the time was right. But the moment I moved back to my dad’s, I had a mental breakdown. I was unemployed, unemployable, making esoteric work for which there was clearly a very small audience, if at all. I felt undateable, unlovable. And there was no way I would be able to move to London or New York and build a life.

Everything had gone belly up. And, in hindsight, not without reason. These were all products of mistakes that I’d made. Reaching that low point, in which I was unable to sleep and completely suicidal, was also a blessing in a way, because it was the first time I got help. I found a therapist I liked. I started taking medication. And I gained clarity. At the age of 26, I realized I needed to build my life from scratch. Melbourne was too populated with ghosts. So I booked a ticket to New York!

A fresh start in New York

In New York City, I hit the ground running. I called in every favor to find a job of any kind. And I ended up taking a job as a sort of aide de camp for a creative director who had his own practice. I was contracted to do his dirty work. In art school I’d learned lots of skills—I can shoot and edit video pretty proficiently and I’m decent with Photoshop. Which ended up making me really useful for this guy. He asked me if I knew how to code. I didn’t. So I taught myself.

I was living above Union Square then, and while taking the train from there I noticed all of these ads using illustrations. Since I was a sponge and open to any opportunity, I realized how ubiquitous illustration was here, not just in advertising but in editorial. It seemed serious and had authority. It really appealed to me. So, as I was working for this guy, I decided to build up my skills properly again. To make myself available for illustration work. To put myself out there. To transform my social media from irreverence to a shockingly earnest portfolio. And after about a year of this, I was able to work as an illustrator full time.

‘My first gig? The New York Times’

Before I moved here, the idea of working for the New York Times or the New Yorker was completely inconceivable. They’re these titans and I’m a kid from Melbourne. Only gods could contribute to them. But of course, when you move here, you realize they take a lot of chances on young artists.

T, The New York Times Style Magazine, which is edited by Hanya Yanagihara—who’s since been a consistent champion of my work—had hired a very experienced artist, one of my heroes, to do an extremely detailed two-page spread for an issue about NYC in the 1980s. It was the centerpiece of the issue. But a week before print, this artist informed them he could no longer do it. So they were in a panic figuring out a plan B.

During late nights after I’d finished work on the Lower East Side, I used to make party invitations for friends. It was psychotic how much work I put into them, entirely with the philosophy that I didn't know who was going to see them. And one of those invitations ended up with someone who worked at the Times! Because I made these detailed drawings that seemed to translate well into print, I was ID’d as someone who could potentially step in to handle the job. They probably knew I was young and hungry enough to take it on despite the tight timeline. I had six days to do five complex and rigorously researched drawings. Now I’m a lot faster, but still not that fast. If someone approached me with the project now, I’d say absolutely not!

Career liftoff

The story blew up and within a week or two I had three offers for US representation. So, while it had all been a very gradual, long road and a pretty shaky one, I can definitely point to this project as the moment it became serious. And I’ve been on that road ever since. One of the highlights since then was a campaign I did for Red Bull that was actually showcased in Union Square Station. They did a whole takeover and printed these enormous things. It felt very wonderful and circular!

Creating something real

In an ideal world, I’d love to just focus on books and exhibitions. I’m currently negotiating two children’s books, which I’ve never done before. And I have a museum show in Seoul opening in September, which has been keeping me busy! I’m showing around 300 works in seven rooms.

Although the world has changed a lot, kids still love picture books. And people still love seeing physical work, made by hand, on walls. These are the things that remind us of being human. I hope my work encourages a slightly slower consumption. There’s a notion that young people no longer have the attention span for this stuff, or don't have the appetite to spend their time this way. But I don't think that’s true.

The perils and promise of AI

If I were a cynic, I’d say we're all f*cked, but I don’t have the time or inclination to entertain that sort of thing. Because, if you believe that, why go on? The optimist in me thinks that the existential threat posed by our potential robot overlords is something that will encourage community and thoughtfulness rather than abandoning with humanity altogether.

I mean, mass manufacture has existed for a very long time, but people still enjoy handmade things. I hope that AI will encourage people to become more thoughtful viewers and think more about the labor behind art. Will AI replace artists? I’m not convinced. Will artists need to adapt? Absolutely. Artists will increasingly need to remind their audiences that there is a real person behind their images. That’s not necessarily the worst thing in the world.

What I’ll be doing 20 years from now

I’ve always been fascinated when artists have unrelated ventures. Like the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who opened a cafe-restaurant in Manhattan in the 1970s, which was, by many accounts, the first place in New York where many people tried sushi. Or the Italian artist Alighiero Boetti, one of my all-time favorites, who ran a small hotel in Kabul in the 70s and 80s before the Soviet invasion.

Then there are artists who stop making work altogether. Marcel Duchamp announced he had done everything with art that could be done; that he’d spend the rest of his days focusing on chess. A lot of people lionize that. A lot of people don’t. Yet Duchamp was secretly assembling an installation artwork, now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, that’s not only one of his most remarkable works, but one of the most remarkable works of art in the world!

What am I going to be doing in 20 years? It’s important to be a thermometer of your needs and desires. If I run out of things to say or lose love for what I do, that’s something to listen to. But those feelings come and go. There are days when I’m completely fed up and days when I’m in love again. But whether I’m still drawing or if I’ve moved on to painting or filmmaking or something else, I still want to be making images and telling stories of what it feels like to be alive.

ILYA’S 6 BIG LESSONS

1. Be self aware

Recognize your limits. Mine are significant. I’m pretty good at some things, but technically I’m a complete hack compared to the great artists of previous eras and artists today who are capable of a degree of precision I’ll just never have. I still draw everything by hand, even though it's inefficient. And I use pretty poor tools. Literally every drawing I've done has been with a $3 Fineliner, which I’ve loved since I was twelve or thirteen.

2. Consistency is key

When I started, I looked closely at what other illustrators were doing. Some were really adaptable and had different styles. That didn’t really appeal to me. I’m a huge fan of the French filmmaker Robert Bresson. He wrote a book I love called Notes on the Cinematographer and he shot all of his later films using a 50 millimeter lens. Bresson wrote something like, ‘A filmmaker constantly changing their lens is like someone constantly changing their glasses.’ I feel this way about my style.

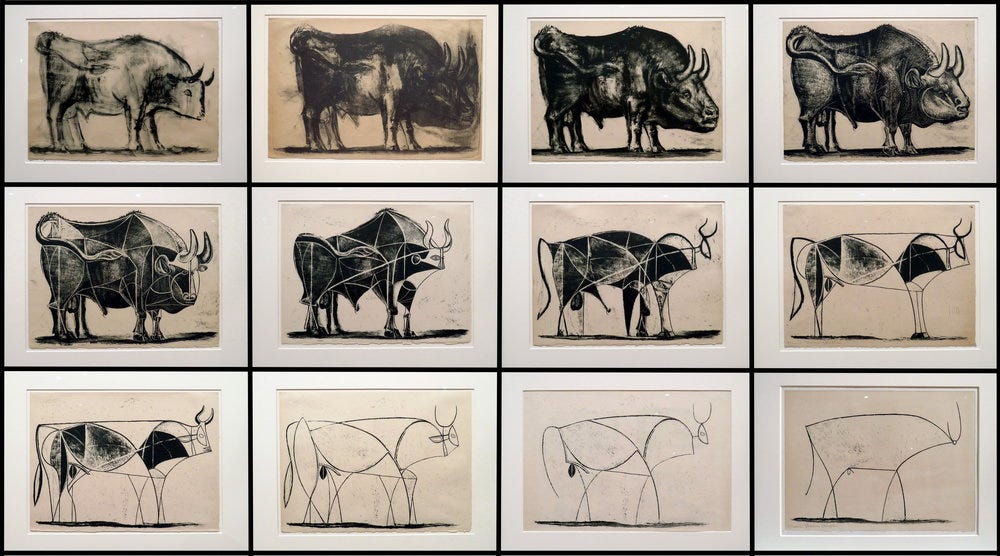

Consistency matters. You don't want to be a pendulum swinging with trends. It’s better to stick with what you do. Your thing might come in and out of favor, but that’s okay. There’s that Picasso study of a bull. I’d hope that if I’m drawing a bull from a certain angle twelve times, I’ll have twelve identical drawings. Because I’m trying to describe a consistent and coherent world and for it to be its own reality.

3. Think of the long-term

For anyone starting something new, there’s an initial period of excitement. When I got my first email from the New Yorker asking if I wanted to illustrate an article, which had been my dream for a very long time, I got up from my desk—without answering the email—walked the four flights of stairs from my studio to Elizabeth Street in Chinatown, and circled the block a few times, just to clear my head and exert energy. It was such an out-of-body experience. But of course, with time, it’s hard to be that excited by new things. So where else can you go from that point? For me, it’s about long term sustainability.

4. Passion above all

The credo I’ve heard from a lot of creative people is that you can put in 80% of the effort and get 95% of the results. While I understand that, it’s also a really easy way to completely fall out of love with what you’re doing. Maintaining your passion is absolutely critical. If you get too tied up in making money, it will never feel like enough. You’ll end up resenting people who took different career paths. And if you get too tied up in being prolific when it’s not in your nature, you’ll burn out and the quality of your work will suffer.

5. Learn from the lows

The lows in my life ended up being hugely instructive. Insecurity made me a much better judge of my own work and pushed me to be better. Financial stress and bleakness about my future forced me to make more informed decisions about how I approach my career. I really needed hard knocks to get to where I am. And if you survive them… well, like the cliche, what doesn’t kill you...

6. Slow is better

A couple of years ago, I was taking on more work than I could handle and churning out work that was of a lower quality than I would have liked. During that period, I really didn’t enjoy drawing. But for the past year or two I’ve slowed down and I’ve been more selective about what I work on. I try to commit more energy and thought to each major project. The result? My drawing has improved significantly. And my joy for the process is higher than at any point since I was a kid. I really love working right now. When I have moments of fluency—and the longer they last, the better—I’m at my happiest.

Go deeper… Ilya’s website / Ilya on IG

—

Until next time,

Incredible interview/article! Big fan of Ilya's work myself, since a while (actually just looking at one of his prints in my office) Subscribed and curious to read more!